Country music, at least in its most familiar form, is often defined by images of Southern singers telling stories of heartbreak, hardship, and long nights softened by song. In its earliest days, the genre functioned as a voice for people on the margins, a space where loss, labor, and survival could be spoken plainly. Over time, country music expanded its themes and sounds, yet it has often struggled to fully connect with audiences beyond the United States.

Modern country music emerged as a reflection of American identity, shaped by the social and political realities of postwar America. Early pioneers such as Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, and Kitty Wells embraced a raw, honky-tonk style built on twangy guitars, steel pedals, and unfiltered storytelling. Their music mirrored the struggles of working-class life and carried an emotional directness that defined the genre’s foundation.

By the 1950s and 1960s, country began to smooth its edges. The rise of the “Nashville sound,” led by producers like Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley, introduced orchestration and polished arrangements designed to appeal to a wider audience. Artists including Patsy Cline, Jim Reeves, and Eddy Arnold found crossover success, helping country music reach listeners far beyond its rural roots.

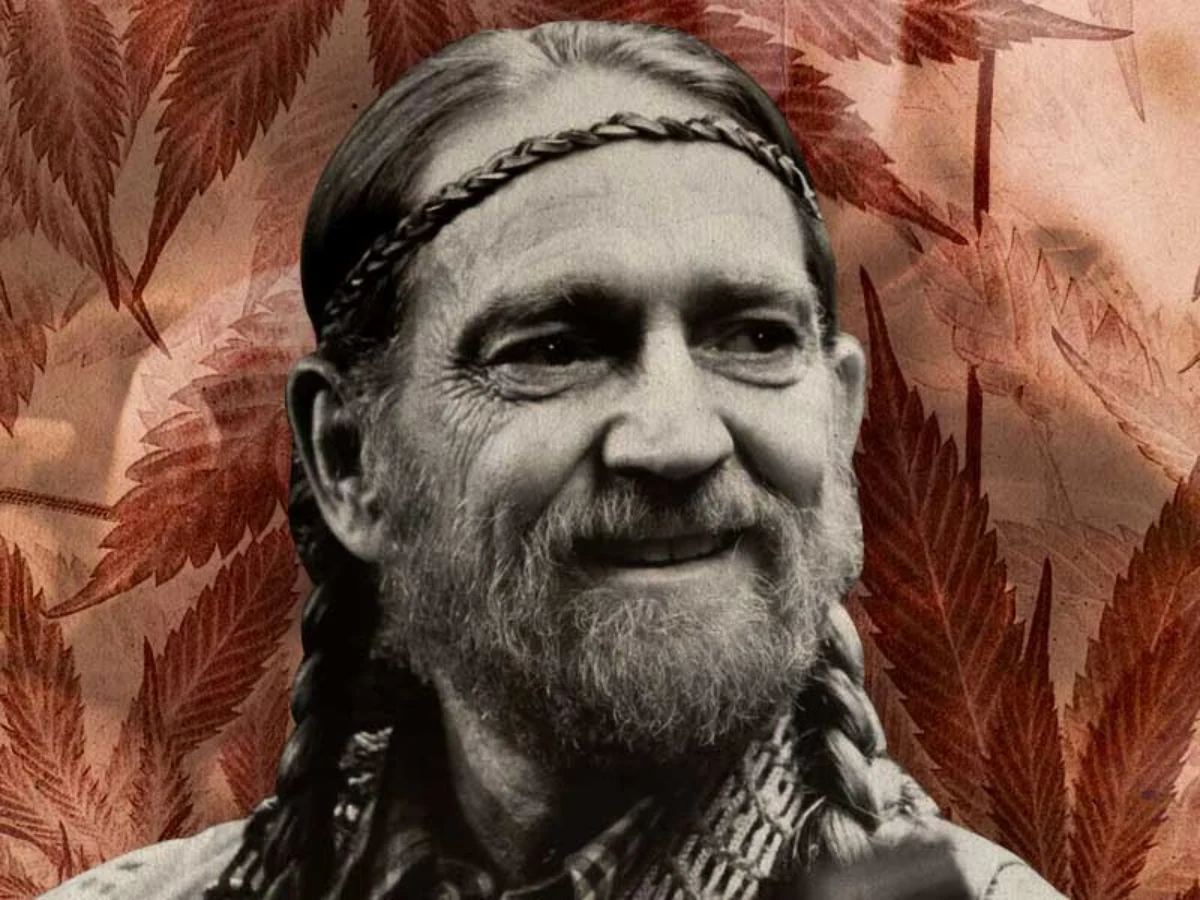

The 1970s ushered in a rebellion against this refinement. Outlaw country figures such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Merle Haggard rejected Nashville’s constraints in favor of creative freedom and grit. Their music championed individuality and resistance, while artists like Dolly Parton broadened the genre’s emotional range and narrative perspective, welcoming new audiences without abandoning its core.

Despite its evolution, country music remains closely tied to American values and national identity. Its themes often emphasize resilience, unity, and loyalty to tradition, reflecting deeply rooted cultural ideals. As historian Eric Stein observed, while other genres came to represent protest movements or countercultures, country music largely defended and reinforced traditional American values.

This connection can make the genre feel culturally specific. Visual symbols like cowboy hats, boots, rural imagery, and pickup trucks may not resonate universally, and access to contemporary country artists can be limited outside the U.S. While global stars like Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, and Willie Nelson have crossed borders, newer voices often remain unfamiliar to international audiences.

Moments of national crisis have further cemented country music’s role as a cultural anchor. Songs such as Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue,” released in the wake of personal loss and the September 11 attacks, demonstrated the genre’s ability to rally, comfort, and unify Americans during times of uncertainty.

Ultimately, country music’s enduring power lies in its role as a reflection of American experience. While it continues to evolve and diversify, its strongest resonance remains domestic, offering reassurance and familiarity during the nation’s most turbulent moments. In that way, country music stands as both an artistic tradition and a cultural refuge, deeply woven into the fabric of American life.