What kind of man takes his dying dog on one final ride across America instead of quietly saying goodbye in a clinic? I’ve asked myself that question a hundred times, and every time, the answer feels both foolish and true: a man who loved her too much to let her die anywhere except beside him, with wind on her face and the world rolling out in front of her.

The first cough came in the middle of a winter night. Rosie jolted me awake with a sound so small it barely belonged to her. Fifteen years—fifteen long, loud, joyful years—and I had never heard her sound weak. Rosie wasn’t just a dog. She’d been my wife’s before she was mine, a rescue mutt with one torn ear, mismatched tan-and-white fur, and eyes too full of knowing to ignore. When my wife brought her home, Rosie was half-starved and scared of every sudden movement. A dog that had lived a hard life before she ever found us.

But she’d bloomed. My wife used to say Rosie had a soul older than ours. When cancer took her, when the house went cold and silent and every corner felt like a place I’d lost something, Rosie stayed. She didn’t leave my side, not for a minute. In those first grief-heavy nights when I couldn’t sleep, when the world felt like it had shrunk into a knot of pain inside my chest, Rosie stayed pressed against me, breathing slow and steady, anchoring me to something that still felt alive.

Two weeks before the ride, the vet said the words I didn’t know how to swallow.

“It’s time to prepare,” she said softly, her hands gentle but her eyes sure. “Her lungs are failing. She’s fading fast.”

I’m seventy-two years old. I’ve buried brothers from the war. I’ve buried biker brothers on the sides of highways that still smell like gasoline and loss. I’ve buried the woman who kept me human. I thought I knew how grief worked—how it hit, how it settled, how it scarred. But the thought of burying Rosie cracked something in me that none of those other losses had touched.

That night, in the fading light of a life I knew was slipping away, I made a promise. Not to myself, and not to any God I’m not sure listens. I made it to her.

“Girl,” I whispered, running a hand over her thinning fur, “I’m not letting you go out in a cold clinic on a metal table. You’re going out the way you lived. Wind on your face. With me beside you. I promise.”

The next morning, I walked out to the shed behind the house and stared at the old Harley sitting beneath a tarp. The chrome was dull, the paint chipped from decades of roads and stories, but when I turned the key, the engine still rumbled like an oath given shape. The sound filled the air, thick and familiar, and for a moment I felt twenty instead of seventy-two.

I pulled out the sidecar too, brushed off the dust, and lined it with Rosie’s favorite blanket. Then I strapped in a tiny pair of dog goggles I’d bought years ago as a joke but never actually used. Rosie saw me prepping the bike and tail-wagged once—slow, gentle, but certain. That was enough. She understood.

We weren’t just taking a ride. We were taking the ride. The last one.

We rolled out onto the two-lane backroads of Ohio, the morning sun low and pale. Rosie sat upright in the sidecar, her head lifted as far as her strength allowed, her torn ear flapping in the wind. Every time I glanced over, she looked happier than she had in months. Almost like she was thanking me.

At first it was just the two of us. Me, an old man trying not to think too far ahead, and Rosie, an old dog leaning into her final moments with more grace than I thought possible. We headed south, toward Kentucky, sticking to backroads and quiet towns where the world moves slow enough to notice small things.

But word travels fast in the brotherhood.

By the time we crossed into Kentucky, Big Ray was waiting at a gas station, leaning against his Harley like he knew exactly when we’d arrive. He didn’t ask why. He didn’t need the story. He just looked at Rosie, then at me, and nodded. That was enough. He fell into formation beside us.

In Tennessee, two more joined. In Alabama, five more—old bikers with weathered faces, younger ones with nervous hands, men who had buried dogs and wives and brothers and parts of themselves they didn’t talk about. All of them joining without needing a single word.

By the time we reached the Gulf, there were a dozen of us. A ragtag honor guard, engines rumbling low and slow, riding at Rosie’s pace. People stared, took pictures, waved, but no one laughed. No one even smiled the wrong way. Because there was something holy—yes, holy—about a dying dog wearing goggles in a sidecar, surrounded by men who understood what it meant to love something that wouldn’t last forever.

At every stop, Rosie got weaker. Her legs shook when she tried to stand. Her breathing turned shallow, then ragged. But each time we started that engine, she lifted her head. As if the sound alone kept her tethered to life.

Our destination wasn’t random. The Gulf wasn’t just a place. It was unfinished business.

My wife had always dreamed of taking Rosie to the coast—letting her chase seagulls, dig crazily into the wet sand, bark at waves like they were living things. But life got in the way. Bills, illness, treatments, hope, more treatments, and then the end that none of us were ready for. We never made that trip. And I refused to let death steal that dream from either of them.

We reached Gulf Shores as the sun melted into the horizon, that deep orange glow spreading across the water. The salty air rolled over us, warm and thick, and something in Rosie changed. She perked up, her cloudy eyes gaining a flicker of recognition, as if some part of her had been waiting for this moment all along.

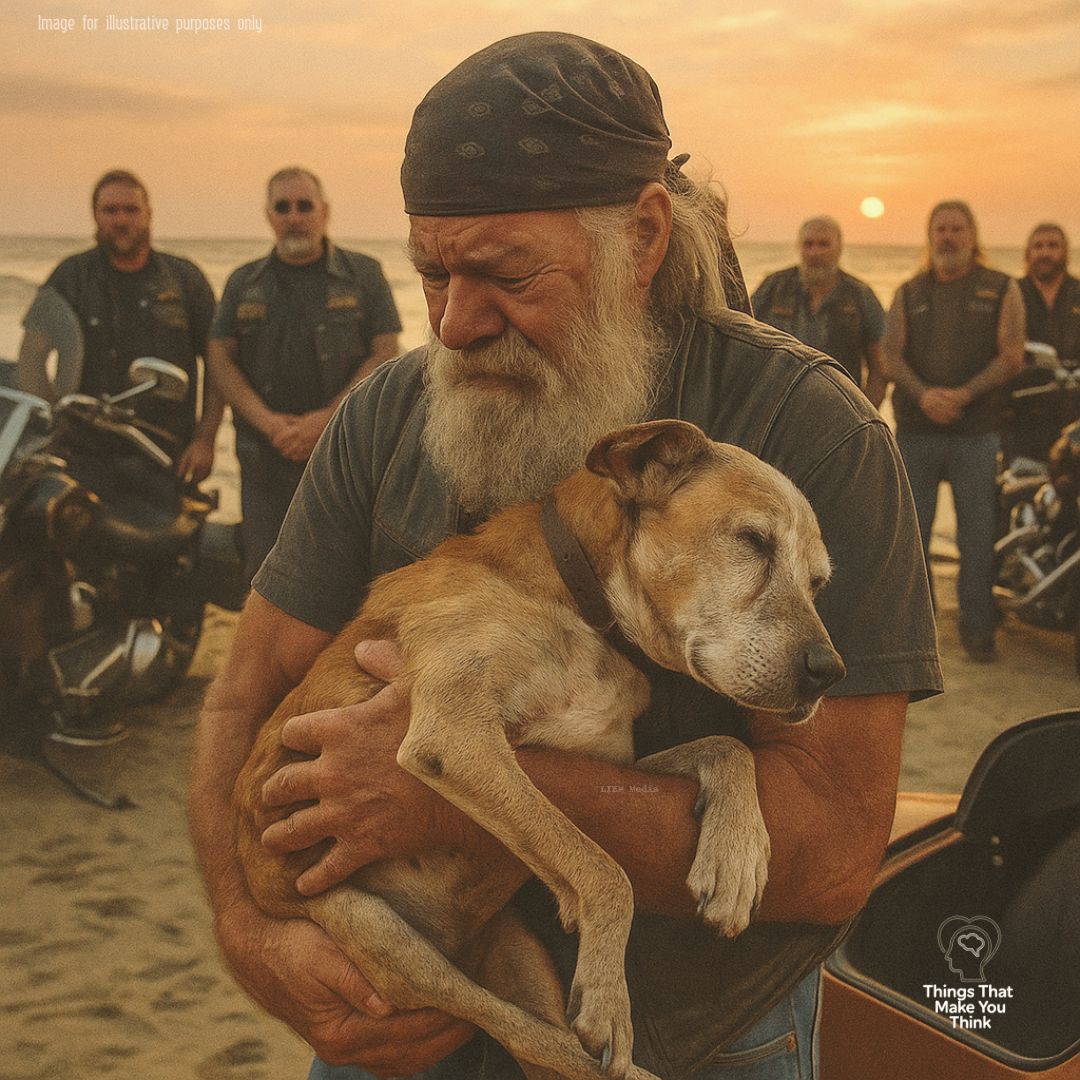

I turned off the engine. The brothers formed a circle around us, bikes idling like an unspoken prayer. I lifted Rosie from the sidecar—my God, she was so light—and carried her toward the water. Her fur brushed my cheek, and for a moment, I swear I could feel my wife beside me, walking with us.

Rosie’s paws touched the sand. She took one trembling step, then another. For that brief moment, she looked like the pup she had once been—curious, alive, the wind hugging her like an old friend. She walked right to the waterline, let the waves roll over her paws, and turned back to me.

And that was her last step.

She collapsed softly, like she was folding into sleep. No cry, no whimper. Just one long, quiet sigh, as if she’d been holding her breath for years and finally let it go. Her head rested against my boot. Her eyes closed. And Rosie was gone.

The world didn’t pause. The waves kept rolling. The wind kept blowing. But something inside me settled in a way grief rarely allows. She hadn’t died in a cold room on a metal table. She had died with the ocean at her feet and the man who loved her more than he understood standing right beside her.

That night, under the open sky, I buried her ashes in the sand. The brothers stood silent, hands on shoulders, hats off, engines still cooling behind us. I didn’t cry. Not then. Bikers aren’t supposed to cry, or at least that’s the lie we tell ourselves. But when the engines roared to life as one, shaking the ground like distant thunder honoring a fallen friend, something inside me cracked. Tears came. Hot, messy, unstoppable. And no one judged me for it.

Because every man there had loved something fiercely. And lost something fiercely too.

The road teaches you that everything ends—rides, nights, lives. But Rosie taught me something else: loyalty doesn’t end, not even when the heart that carried it stops beating.

The next morning, I strapped her empty blanket back into the sidecar. I rode home with the brothers at my side, the wind carrying pieces of her memory in every gust. And in that empty space where she used to sit, I swear I felt her still—head lifted, ear flapping, ready for wherever the road might take us next.

People ask why I did it. Why I didn’t just let her go peacefully in a vet’s office. Why I rode hundreds of miles with a dying dog beside me.

The truth is simple.

Love deserves effort. Loyalty deserves more than quiet endings. And promises—especially the ones whispered to old dogs in dark rooms—should be kept.

So if you love something, don’t wait. Don’t say “someday.” Don’t plan the trip for next year, or the year after that. Take the ride now. Make the memory now. Keep the promise now.

Because one day, someday will be too late.

And when that day comes, all you’ll wish for is one more mile, one more ride, one more moment with the soul who walked beside you for a lifetime.